In this article:

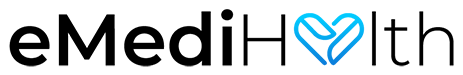

The plantar fascia is a broad ligament (a band of soft tissue that runs from bone to bone) that spans the bottom of the foot. It originates on the inner aspect of the sole of the heel bone (the calcaneus) and spans the sole of the midfoot. The plantar fascia supports the arch of the foot.

Plantar fasciitis, or inflammation of the plantar fascia, occurs when the ligament becomes inflamed at its origin on the heel bone. The inflammation may also be accompanied by microtearing in the ligament (small tears) as the condition progresses or even rupture of the ligament in severe, chronic (long-term) cases.

In long-term cases, inflammation can be seen in the bone near the ligament with possible formation of a bone spur.

This article discusses the various causes of plantar fasciitis, people who are at higher risk of developing it, and the ways in which it can be effectively managed.

How Common Is Plantar Fasciitis?

Most cases of heel pain in adults are attributed to plantar fasciitis, which accounts for 11%–15% of all the foot complaints that require medical attention.

One in every 10 individuals gets affected by plantar fasciitis at some point in their life. (1)

Common Causes and Risk Factors

Plantar fasciitis has several causes, and some people may be predisposed to it. Some common causes of the condition and its risk factors include the following:

- Wearing shoes that are very flat or with poor arch support is a very common cause of plantar fasciitis. In women, very flat sandals and ballerina flats are common culprits.

- Overuse may also cause plantar fasciitis and heel pain. This is particularly common in runners, athletes, factory workers, teachers, and whoever spend a lot of time on their feet.

- Injury or trauma to the sole of the foot may also cause problems with the plantar fascia.

- People who are overweight may be predisposed to the condition. (2)

- Pregnancy also may increase one’s chances of developing the condition, as pregnancy hormones and the excess weight affect the ligament.

- Diabetics are also more susceptible to this problem. (3)

- People with tight calf muscles (4) have an increased risk of developing plantar fasciitis.

Symptoms of Plantar Fasciitis

Most patients will complain of “startup” pain at the bottom of the foot. This means that after a period of sitting or inactivity, such as sleeping, the first initial steps can be quite painful, even causing them to limp for a period of time.

After the plantar fascia “warms up,” the symptoms can improve dramatically until the next period of inactivity. In moderate to severe cases, pain can be present constantly. Pain can be sharp initially and then may progress to a dull ache or throb. Some people may also experience tearing pain.

These symptoms occur as the plantar fascia remains in a rested, contracted (or shortened) position when you are not standing. Upon standing, the ligament stretches as your arch flattens and essentially pulls away from its origin, causing pain. As it loosens up over time, the pain then improves.

Unfortunately, plantar fasciitis can last for several months even with daily and active treatment. In fact, the average duration of plantar fasciitis symptoms is 6–9 months. (1) Beyond that time frame, it is considered chronic.

Conservative Treatment for Plantar Fasciitis

Most cases of plantar fasciitis can be successfully managed through a number of noninvasive measures, but it can take several months to make a full recovery.

1. Physical therapies

There are a couple of stretching exercises to strengthen lower leg muscles.

a. Plantar fascia stretch

According to research, the most effective treatment for plantar fasciitis is the plantar fascia stretch.

It is important that stretching occurs BEFORE standing, such as first thing in the morning or after prolonged sitting. Also, care should be taken not to overstretch; stretching should not be painful.

How to perform:

- Grab the toes and pull them upward while simultaneously pulling the ankle upward. This is best performed by crossing the affected leg over the opposite thigh.

- If you are unable to reach your toes, use a towel or resistance band along the bottom of the foot while sitting and pulling upward.

- Hold the stretch for 30–60 seconds.

- Perform this exercise at least 3–5 times per day.

b. Achilles tendon stretch

Tightness of the Achilles tendon often accompanies plantar fasciitis, and Achilles stretching should be incorporated into any plantar fascia stretching regimen assuming there is no injury to the Achilles. This is best accomplished by performing a “runner’s Achilles stretch” against a wall.

How to perform:

- Place the affected leg straight behind you with the heel flat and the toes pointed straight.

- Bend the opposite leg at the knee just below your hips, place your hands on the wall at shoulder level.

- Hold the calf stretch for approximately 30 seconds.

- Repeated 3 times on each leg.

2. Orthotics

Orthotics such as viscoelastic heel cups have also been shown to provide improvement in the symptoms.

A good pair of over-the-counter insoles (insoles that don’t collapse under your body weight) from a running store or pharmacy has been shown to be comparable to custom orthotics for the vast majority of patients.

Patients that have failed over-the-counter orthotics, have a severe flat foot, or have a very high arch may benefit from custom orthotics that can be ordered by the treating physician.

3. Arch support

Arch should also be extended into the home with a pair of house shoes, such as slip-on mules, with adequate arch support. It is recommended to put these on directly when coming out of bed to reduce the acute stretch on the ligament with standing.

You can also stretch out the arch of your foot by wearing a splint or kinesiology tape, both of which provide temporary relief from plant fasciitis.

4. Activity modification

Activity modification for cases caused by overuse or sports should be incorporated into treatment. Cross-training, low-impact exercises such as swimming or biking, or a period of dedicated rest from the aggravating activity should be instituted.

5. Cold compress

A cold compress can help numb the affected area temporarily so that you feel less pain while the effect lasts.

But you must do this therapy right for it to deliver the desired results, or else it can aggravate tissue damage. For instance, directly applying such freezing temperature to one spot for long periods at a stretch can induce frostbite.

You can use an ice pack or frozen bag of peas as a cold compress. Wrap the compress in a washcloth or towel, and then place it on the affected site for 10–15 minutes, 3–4 times a day.

6. Medications and supplements

A short course (less than 5 days) of over-the-counter anti-inflammatories, such as ibuprofen or naproxen, can also be tried if you have severe daily pain primarily for symptomatic relief.

Naturopathic remedies such as turmeric (5) may also be tried and incorporated into your daily supplements.

Usage of any anti-inflammatory should be approved by your physician.

Note: Home treatments such as banding, foot massages, warm or cold compresses, Epsom baths, or supplements such as ginger, apple cider vinegar, or fish oil, though suggested at some places, have not been scientifically proven to treat plantar fasciitis.

Advanced Treatment Modalities for Plantar Fasciitis

There are some other treatment modalities available to manage plantar fasciitis, but these are recommended only when the conventional and noninvasive measures described above are not working very effectively or if your condition has turned chronic.

1. Steroids for pain relief

Your doctor may administer corticosteroid injections to relieve the pain and inflammation associated with acute or chronic plantar fasciitis. Steroid treatment provides instant results and is quite useful in managing chronic pain conditions that don’t respond to conservative treatment.

However, this treatment is not without its side effects. Prolonged use or overdosage of steroids can progressively wear out your tissues and even rupture the plantar fascia.

2. Surgery

Your doctor may need to surgically lengthen the gastrocnemius tendon (part of the Achilles tendon) when plantar fasciitis becomes so severe that it does not respond to any other treatment modality. This surgery is called gastrocnemius recession or gastrocnemius release, and it is the last resort treatment, which is rarely used.

The general reluctance to go for such invasive measures is due to the complications that may arise later. Foot surgery demands not only proper postoperative care of the incision site but also extensive rehabilitation measures to restore full mobility to the foot.

Also, there’s always the risk of arch flattening, nerve damage, and calcaneal fracture after the operation.

3. Others

Some treatments such as extracorporeal shock wave therapy, (6) ultrasonic tissue repair, and platelet-rich plasma therapy are also used to treat chronic cases of plantar fasciitis, but they are not always successful. The efficacy of these modalities is still being studied.

Diagnosing Plantar Fasciitis

Your doctor will start with a foot examination to understand the state of damage, followed by a thorough review of your medical history.

Your doctor will then inquire about your symptoms: when did they begin, how bad is the pain, is there anything that makes it worse or better, etc.

You may have to undergo tests such as an X-ray, MRI, or ultrasonography to rule out other possible causes of the foot pain and to arrive at a conclusive diagnosis. (7)

Preventing Recurrence

Plantar fasciitis can come back after being resolved, and so you have to take proactive measures to avoid such recurrences. This basically means you need to keep looking after your feet even after recovering from plantar fasciitis to make sure it doesn’t happen again.

Postrecovery podiatric care involves:

- Giving your feet proper rest from time to time

- Wearing well-cushioned footwear to minimize stress on your feet

- Maintaining a healthy body weight

- Switching to low-impact exercises

- Using orthotics if needed

Dietary Changes for Plantar Fasciitis

There are no dietary changes shown to be effective in the treatment of plantar fasciitis.

Plantar Fasciitis vs. Heel Spurs

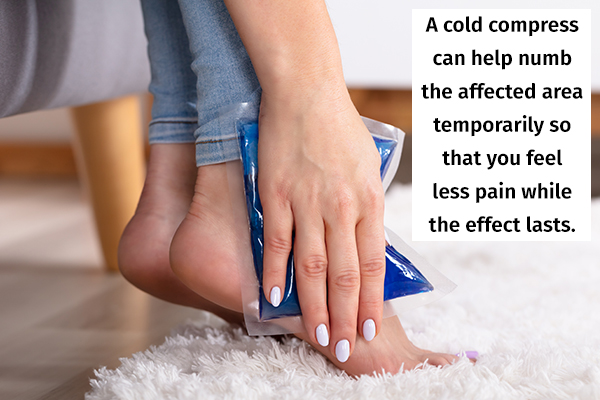

Heel spurs, or traction spurs, are caused by calcium deposition (buildup) in the plantar fascia ligament at the site where the plantar fascia attaches to the heel bone along the sole of the foot. It is believed to be caused by chronic injury (inflammation, tearing, and stretching) to the plantar fascia.

Heels spur can only be diagnosed with advanced imaging such as X-rays.

It is important to note that plantar fasciitis can exist WITHOUT the presence of a heel spur, and a heel spur can be present WITHOUT active plantar fasciitis. In the former, the plantar fascia can be inflamed and injured without any excessive calcification present. In the latter, you can have a heel spur present without any pain or symptoms from the plantar fascia.

Heel spurs are commonly seen on X-rays obtained of the foot for other reasons and should not cause alarm. Therefore, treatment should never be aimed at treating just a heel spur alone.

The heel spur may be inflamed with long-standing plantar fasciitis. This inflammation can only be confirmed with advanced imaging such as an MRI. There is no clear data to suggest that the presence of a heel spur affects the duration of plantar fasciitis, and treatment does not change if a heel spur is present (although this is a topic of some debate across foot specialists).

Final Word

Most cases of plantar fasciitis will resolve with conservative, noninvasive treatment measures, provided you are consistent in your efforts.

Dedicated, frequent daily stretching along with insoles is the best treatment for plantar fasciitis. If these do not work, your doctor may progress to more advanced treatment options and rarely recommend foot surgery if all else fails. You must keep looking after your foot even after recovering because plantar fasciitis tends to recur.

- Was this article helpful?

- YES, THANKS!NOT REALLY